Begging (also

panhandling or

mendicancy) is the practice of imploring others to grant a favor, often a gift of

money, with little or no expectation of reciprocation. A person doing such is called a

beggar,

panhandler, or

mendicant. Street beggars may be found in

public places such as transport routes, urban parks, and near busy markets. Besides money, they may also ask for food, drink, cigarettes or other small items.

Internet begging is the modern practice of asking people to give money to others over the internet, rather than in person. Internet begging is usually targeted at people who are acquainted with the beggar, but it may be advertised to strangers. Internet begging encompasses requests for help meeting

basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter, as well as requests for people to pay for

vacations,

school trips, and other things that the beggar wants but can't comfortably afford.

History[edit]

Beggars have existed in human society since before the dawn of recorded history. Street begging has happened in most societies around the world, though its prevalence and exact form vary.

A beggar in

Uppsala, Sweden. June 2014.

Ancient Greeks distinguished between the

penes (Greek: ποινής, "active poor") and the

ptochos (Greek: πτωχός, "passive poor"). The

penes was somebody with a job, only not enough to make a living, while the

ptochosdepended on others entirely. The

working poor were accorded a higher social status.

[1] The

New Testament contains several references to

Jesus' status as the savior of the

ptochos, usually translated as "the poor", considered the most wretched portion of society.

Britain[edit]

A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, vulgarly called vagabonds, was first published in 1566 by

Thomas Harman. From early modern England, another example is

Robert Greene in his

coney-catching pamphlets, the titles of which included "The Defence of Conny-catching," in which he argued there were worse crimes to be found among "reputable" people.

The Beggar's Opera is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay.

The Life and Adventures of Bampfylde Moore Carew was first published in 1745. There are similar writers for many European countries in the early modern period.

[citation needed]

According to

Jackson J. Spielvogel, "Poverty was a highly visible problem in the eighteenth century, both in cities and in the countryside... Beggars in Bologna were estimated at 25 percent of the population; in Mainz, figures indicate that 30 percent of the people were beggars or prostitutes... In France and Britain by the end of the century, an estimated 10 percent of the people depended on charity or begging for their food."

[2]

The British

Poor Laws, dating from the

Renaissance, placed various restrictions on begging. At various times, begging was restricted to the

disabled. This system developed into the

workhouse, a state-operated institution where those unable to obtain other employment were forced to work in often grim conditions in exchange for a small amount of food. The

welfare state of the 20th century greatly reduced the number of beggars by directly providing for the basic necessities of the poor from state funds.

In India[edit]

A street beggar in

India gets into a car

Begging is an age old social phenomenon in India. In the medieval and earlier times begging was considered to be an acceptable occupation which was embraced within the traditional social structure.

[3] This system of begging and alms-giving to mendicants and the poor is still widely practiced in India, with over 400,000 beggars in 2015.

[4]

In contemporary India, beggars are often stigmatized as undeserving. People often believe that beggars are not destitute and instead call them professional beggars.

[vague][5][better source needed] There is a wide perception of begging scams.

[6] This view is refuted by grassroots research organizations such as Aashray Adhikar Abhiyan, which claim that beggars and other homeless people are overwhelmingly destitute and vulnerable. Their studies indicate that 99 percent men and 97 percent women resort to beggary due to abject poverty, distress migration from rural villages and the unavailability of employment.

[7]

Religious begging[edit]

A mendicant outside ‘

Kalkaji Mandir’ in Delhi, India

Many religions have prescribed begging as the only acceptable means of support for certain classes of adherents, including

Hinduism,

Sufism,

Buddhism, and typically to provide a way for certain adherents to focus exclusively on spiritual development without the possibility of becoming caught up in worldly affairs.

Religious ideals of ‘

Bhiksha’ in Hinduism ,‘

Charity’ in Christianity besides others promote alms-giving.

[8] This obligation of making gifts to God by alms-giving explains the occurrence of generous donations outside religious sites like temples and mosques to mendicants begging in the name of God.

Tzedakah plays a central role in Judaism. According to the Torah, Jews are obligated to contribute 10% of their income as tithes, which also can include giving to the poor.

In

Buddhism,

monks and

nuns traditionally live by begging for

alms, as done by the historical

Gautama Buddha himself. This is, among other reasons, so that

Laity can gain religious merit by giving food, medicines, and other essential items to the monks. The monks seldom need to plead for food; in villages and towns throughout modern

Myanmar,

Thailand,

Cambodia,

Vietnam, and other Buddhist countries, householders can often be found at dawn every morning streaming down the road to the local temple to give food to the monks. In East Asia, monks and nuns were expected to farm or work for returns to feed themselves.

[9][10][11]

Ming China was founded by former beggar

Zhu Yuanzhang. Orphaned in childhood due to famine,

Zhu Yuanzhang, turned to the Huangjue temple for help. When the temple ran out of resources to support its occupants he became a

mendicant monk traveling China begging for food.

[12]

Legal restrictions[edit]

A kindness meter in downtown

Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada. The meter accepts donations for charitable efforts to help the poor as part of an official effort to discourage panhandling.

Begging has been restricted or prohibited at various times and for various reasons, typically revolving around a desire to preserve

public order or to induce people to

work rather than to beg for

economic or

moral reasons. Various European

poor laws prohibited or regulated begging from the

Renaissance to modern times, with varying levels of effectiveness and enforcement. Similar laws were adopted by many developing countries such as India.

"

Aggressive panhandling" has been specifically prohibited by law in various jurisdictions in the United States and Canada, typically defined as persistent or intimidating begging.

[13]

Australia[edit]

Each State and Territory has individual laws regarding begging and panhandling.

In South Australia, begging for

alms is illegal, and may bring a maximum penalty of $250. This legislation is outlined in the Summary Offences Act 1953 - Section 12

[14]

Austria[edit]

There is no nationwide ban but it is illegal in several federal states.

[15]

Begging in China is illegal if:

- Coercing, decoying or utilizing others to beg;

- Forcing others to beg, repeatedly tangling or using other means of nuisance.

Those cases are violations of the Article 41 of the Public Security Administration Punishment Law of the People's Republic of China. For the first case, offenders would receive a detention between 10 days and 15 days, with an additional fine under

RMB 1,000; for the second case, it is punishable by a 5-day detention or warning.

According to Article 262(2) or the Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China, organizing disabled or children under 14 to beg is illegal and will be punished by up to 7 years in prison, and fined.

[citation needed]

Ming China[edit]

After the establishment of the

Ming Dynasty many farmers and unemployed laborers in

Beijing were forced to beg to survive.

[20] Begging was especially difficult during Ming times due to high taxes that limited the disposable income of most individuals.

[21] Beijing's harsh winters were a difficult challenge for beggars. To avoid freezing to death, some beggars paid porters one copper coin to sleep in their warehouse for the night. Others turned to burying themselves in manure and eating

arsenic to avoid the pain of the cold. Thousands of beggars died of poison and exposure to the elements every year.

[20]

Begging was some people's primary occupation. A

Qing Dynasty source describes that "professional beggars" were not considered to be

destitute, and as such were not allowed to receive government relief, such as food rations, clothing, and shelter.

[22] Beggars would often perform or train animals to perform to earn coins from passerby.

[21] Although beggars were of low status in Ming, they were considered to have higher social standing over prostitutes, entertainers, runners, and soldiers.

[23]

Some individuals capitalized on beggars and became "Beggar Chiefs". Beggar chiefs provided security in the form of food for beggars and in return received a portion of beggars daily earnings as tribute. Beggar chiefs would often lend out their surplus income back to beggars and charge interest, furthering their subjects dependence on them to the point of near slavery. Although beggar chiefs could acquire significant wealth they were still looked upon as low class citizens. The title of beggar chief was often passed through family line and could stick with an individual through occupational changes.

[23]

Denmark[edit]

Begging in Denmark is illegal under section 197 of the penal code. Begging or letting a member of your household under 18 beg is illegal after being warned by the police and is punishable by 6 months in jail.

[15][24]

Finland[edit]

Begging has been legal in Finland since 1987 when the poor law was invalidated. In 2003, the Public Order Act replaced any local government rules and completely decriminalized begging.

[25]

A law against begging ended in 1994 but begging with aggressive animals or children is still outlawed.

[15]

A woman begging at traffic lights in

Patras, Greece.

Under article 407 of the Greek Penal Code, begging was punishable by up to 6 months in jail and up to a 3000 euro fine. However, this law was repelled in November 2018, after protests from street musicians in the city of Thessaloniki.

[15]

Hungary[edit]

Hungary has a nationwide ban. This may include stricter related laws in cities such as

Budapest, which prohibits picking things from rubbish bins.

[15]

Begging is criminalized in cities such as Mumbai and Delhi as per the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, BPBA (1959).

[26] Under this law, officials of the Social Welfare Department assisted by the police, conduct raids to pick up beggars who they then try in special courts called ‘beggar courts’. If convicted, they are sent to certified institutions called ‘beggar homes’ also known as ‘

Sewa Kutir’ for a period ranging from one to ten years for detention, training and employment. The government of Delhi, besides criminalizing alms-seeking has also criminalized alms-giving on traffic signals to reduce the ‘nuisance’ of begging and ensure the smooth flow of traffic.

Aashray Adhikar Abhiyan and

People's Union of Civil Liberties, PUCL have critiqued this Act and advocated for its repeal.

[27] Section 2(1) of the BPBA broadly defines ‘beggars’ as those individuals who directly solicit alms as well as those who have no visible means of subsistence and are found wandering around as beggars. Therefore, during the implementation of this law the homeless are often mistaken as beggars.

[7] Beggar homes, which are meant to provide vocational training, have been often found to have abysmal living conditions.

[27]

Begging with children or animals is forbidden but the law is not enforced.

[15]

Luxembourg[edit]

Begging in

Luxembourg is legal except when it is indulged in as a group or the beggar is a part of an organised effort. According to

Chachipe a

Roma rights advocacy

NGO 1639 begging cases were reported by Luxembourgian law enforcement authorities. Roma beggars were arrested, handcuffed, taken to police stations and held for hours and had their money confiscated.

[29]

Begging is banned in some counties and there were plans for a nationwide ban in 2015, however this was dropped after the Centre Party withdrew their support.

[15]

The Singing Beggars by Russian painter Ivan Yermenyov c. 1775

Philippines[edit]

Begging is prohibited in the Philippines under the Anti-Mendicancy Law of 1978 although this is not strictly enforced.

[30]

Portugal[edit]

In Portugal, panhandlers normally beg in front of Catholic churches, at traffic lights or on special places in

Lisbon or

Oporto downtowns. Begging is not illegal in Portugal. Many social and religious institutions support homeless people and panhandlers and the Portuguese Social Security normally gives them a survival monetary subsidy.

Romania[edit]

Law 61 of 1991 forbids the persistent call for the mercy of the public, by a person who is able to work.

[31]

US State Department Human Rights reports note a pattern of

Roma children registered for "vagrancy and begging".

[32]

England & Wales[edit]

Begging is illegal under the

Vagrancy Act of 1824. However it does not carry a jail sentence and is not well enforced in many cities,

[33] although since the Act applies in all public places it is enforced more frequently on public transport.

United States[edit]

In May 2010, police in the city of

Boston started cracking down on panhandling in the streets in downtown, and were conducting an educational outreach to residents advising them not to give to panhandlers. The Boston police distinguished active solicitation, or aggressive panhandling, versus passive panhandling of which an example is opening doors at a store with a cup in hand but saying nothing.

[35]

U. S. Courts have repeatedly ruled that begging is protected by the

First Amendment's free speech provisions. On August 14, 2013, the U. S. Court of Appeals struck down a

Grand Rapids, Michigan anti-begging law on free speech grounds.

[36] An

Arcata, California law banning panhandling within twenty feet of stores was struck down on similar grounds in 2012.

[37]

Use of funds[edit]

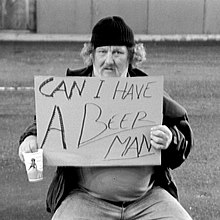

A beggar in Denver, USA in 2018.

A man holding a sign using self-deprecating humor for begging

A 2002 study of 54 panhandlers in Toronto reported that of a median monthly income of $638

Canadian dollars (CAD), those interviewed spent a median of $200 CAD on food and $192 CAD on alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs, according to

Income and spending patterns among panhandlers, by Rohit Bose and Stephen W. Hwang.

[38] The

Fraser Institute criticized this study, citing problems with potential exclusion of lucrative forms of begging and the unreliability of reports from the panhandlers who were polled in the Bose/Hwang study.

[39]

In North America, panhandling money is widely reported to support substance abuse and other addictions. For example, outreach workers in downtown

Winnipeg, Manitoba,

Canada, surveyed that city's panhandling community and determined that approximately three-quarters use some of the donated money to buy tobacco products, while two-thirds buy solvents or alcohol.

[40] In Midtown Manhattan, one outreach worker anecdotally commented to the New York Times that substance abuse accounts for 90 percent of panhandling funds.

[41] This, too, may not be representative since outreach workers work with those with abuse problems.

[citation needed]

Communities reducing street begging[edit]

Please do not Encourage the Beggars

Sarahan, India

Because of concerns that people begging on the street may use the money to support alcohol or drug abuse, some advise those wishing to give to beggars to give gift cards or vouchers for food or services, and not cash.

[40][42][43][44][45][46] Some shelters also offer business cards with information on the shelter's location and services, which can be given in lieu of cash.

[47] This has been criticised since there are typically far fewer shelter beds than people in need.

Notable beggars[edit]

See also[edit]

#PROBEGGER

#PROBEGGER